MCP for EDU

We don’t learn from docs, we learn from doing

This concept has been something I've been kicking around for a while. Recently, I was able to present this as a talk at Apollo GraphQL's MCP Builder meetup in NYC (Thanks, Amanda!). Curious to get your take and how you're using new technologies (like MCP) in your day-to-day learning journeys.

For years, “developer education” has been our polite way of saying read the docs, maybe watch a video, click through the slides, hope for the best. But after running workshops, writing docs, and watching what actually sticks, I’ve realized something’s off: most of what we call “education” isn’t built around how people learn — it’s built around how we document.

We write tutorials and API references as if reading plus repetition equals mastery.

Spoiler alert: it doesn’t.

The best learners — whether athletes, musicians, engineers — don’t simply absorb what they read. They do. They practice, fail, reflect, and adapt. They ask the question, “What happens if I try this?” — in environments that wiggle a little, give feedback, and let them experiment safely.

This process isn’t inherently novel: it’s called "experiential learning" (or constructivist learning): knowledge forms through doing, not just hearing or seeing. The seminal model from David A. Kolb in 1984 spells it out:

And yes — developers know this instinctively. We build, we break, we debug, we re-build. But our scaffolding and our tooling rarely supports that cycle in a way that’s scalable, safe, and measurable.

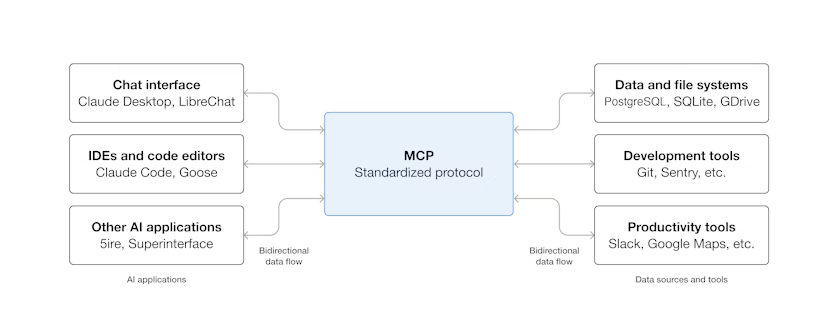

This is part of the reason I’ve been so excited about the potential for the Model Context Protocol (MCP). It isn’t just another platform. In practice, MCP establishes the rules of engagement between a learner and their environment: what tools they can use, what files they can access, and what actions they’re allowed to perform — all with explicit boundaries and observability built in.

Learning as a system

Here’s the paradox: we tell developers to “learn by doing,” but then we hand them slide decks and static code snippets that feel more like worksheets than real systems.

MCP offers potential for addressing this gap, not because we need another “learning tool with badges,” but because we need learning environments that behave like systems. The truth is: most developer-education tools are wrappers — sandboxes that simulate practice but lack the underlying rigor, structure, context, and observability that real systems demand.

MCP changes that. It isn’t a product; it’s a protocol — a technical specification for how agents (human or AI) interact with an environment. It defines what’s accessible and what’s not: which files can be read, which commands can be executed, which systems can be modified — and under what conditions. Every capability is explicit. Every action is permissioned. Every trace is logged.

That level of transparency and governance is what makes MCP so powerful for education. It gives us a framework to design environments that are not only safe, but authentically operational.

When building a workshop, writing a tutorial, or designing a developer-experience demo, the question I keep returning to is: does this environment mirror how engineers actually work? Is it real enough to matter, structured enough to learn safely, and transparent enough to observe progress?

MCP gives us a way to build exactly that. It turns the learning environment from a toy into a controlled system — a place where learners can operate with the same complexity, accountability, and feedback loops they’ll face in production, but with the psychological and technical safety to explore freely.

Put simply: say adios to tutorial hell, and say hello to a living, context-relevant system for learning.

Scaffolding, but make it YAML

Let’s be honest: mastery isn’t winning a one-off hackathon. It’s evolving through stages. One day you’re reading; next you’re tinkering; then you’re deploying with confidence.

My personal learning journey went from MySpace pages and tumblr layouts (♥, anyone?), to API calls, Shopify templates, and then later on to full blown integrations and applications. I explored what I knew, then looked how it fit in a larger picture.

In learning science terms, that’s scaffolding — letting learners operate within their current capability, then nudging them into the next zone. With MCP, we can encode that scaffolding.

Here’s how it might look:

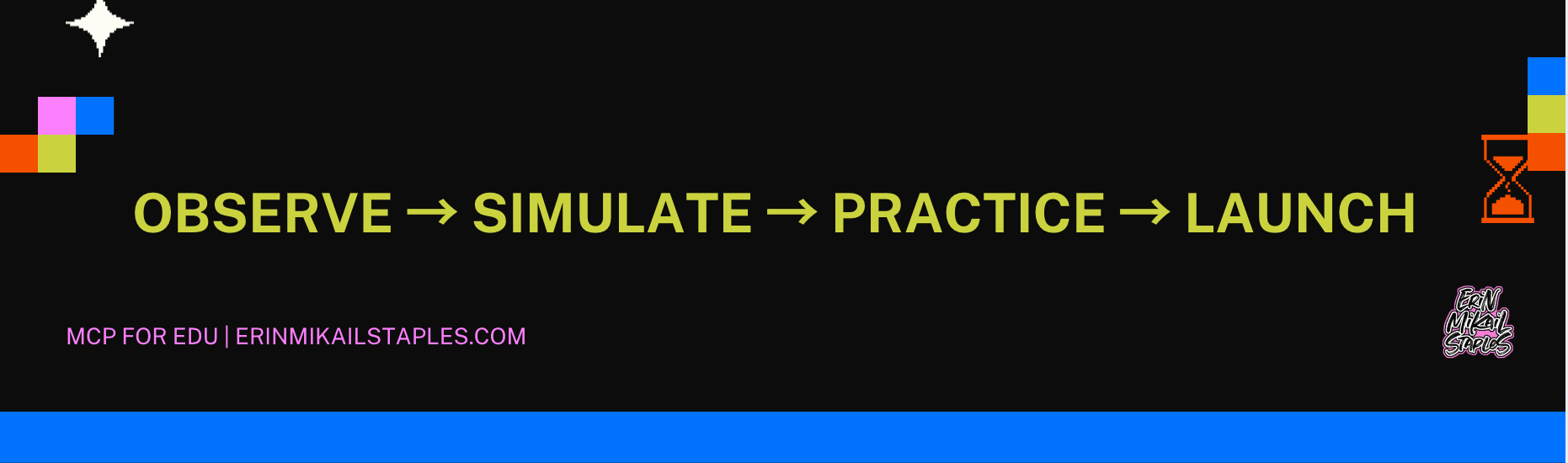

- Observe: You have read-only access; you poke around, explore.

- Simulate: You run commands in a mock mode; you see what “might happen”.

- Practice: You get sandboxed write permissions; you break stuff, revert, fix.

- Launch: You deploy safely in an isolated cluster; you see how things behave at “near production”.

Because these stages are defined in code, progression becomes measurable (not just “you finished xyz”). Just like a CI/CD pipeline moves code from build → test → release, a learner moves through Observe → Simulate → Practice → Launch.

I’ve run plenty of workshops and coached folks through new tools or techniques where learners balk because they “don’t want to break real stuff.” With MCP, that fear fades — because we built the guardrails before letting them drive

Fear creates a terrible learning environment

One of the biggest silent roadblocks to real learning in technical fields isn’t access or skill — it’s fear. “If I push this command, will I crash production?” “If I open this PR, will I look incompetent?” “If I ask this question, will it expose what I don’t know?”

These aren’t irrational anxieties. They’re built into the way most technical environments are structured. Production systems are brittle. Dev environments are under-resourced. Onboarding setups are often an afterthought, riddled with permission gaps and unspoken tribal knowledge.

On most teams, learning and experimentation happen in the margins, not in the design.

The researcher Amy C. Edmondson calls this psychological safety, which is the shared belief that a person can take risks, make mistakes, and ask questions without fear of punishment or humiliation.

In practice, most environments aren’t designed for that. We’ve built systems optimized for uptime and control, not for experimentation or growth. The result? We create environments where curiosity feels dangerous.

This is where MCP offers something radically different. By externalizing safety into the architecture itself — through explicit permissions, reversibility, and complete traceability. When built with proper permissions and guidance, MCP creates conditions where experimentation isn’t just tolerated, it’s designed to be safe.

Learners can act boldly inside real systems, knowing every action is logged, reversible, and scoped. That means psychological safety isn’t dependent on team culture alone — it’s baked into the system’s design.

When you remove the fear of breaking things, you don’t just improve learning. You unlock the full creative bandwidth of the people using your tools.

Turning documentation into runtime

If fear is the thing that holds people back from learning, then documentation is often the silent accomplice.

Think about it: most developer docs are written like instruction manuals for robots — “Here’s how to call the API. Here’s the code snippet. Good luck, bye.” They tell you what to do but not why it works, what happens when it doesn’t, or how to safely explore beyond the example.

That’s where MCP changes everything.

By giving documentation the same scaffolding and guardrails as a live system, MCP lets learners experiment safely. Imagine reading a tutorial and being able to execute each step in a sandboxed environment — no copy-paste roulette, no anxiety about wrecking your setup. You can watch the system respond, review the logs, and tweak parameters, all without fear of breaking something real.

With MCP, docs evolve from static reference to a dynamic runtime experience:

- Instead of copy-pasting commands and holding your breath, you execute in a scoped sandbox.

- Instead of vague stack traces, you get contextual feedback tied to your exact action.

- Instead of unbounded access, you work within safe, defined permissions (

read_only,mock_exec,sandbox). - Instead of stale text, you get live validation tied to the real SDK or manifest behind it.

Docs stop being instruction manuals. They become systems you can learn through.

It’s not just for technical roles

If we can make documentation interactive, why stop there? The same principles that make code more learnable can make anything more learnable. Whether you’re debugging JavaScript or designing a poster, the process is the same — experiment, get feedback, iterate.

And that’s where play comes in.

Retrieval practice (think flashcards, trivia rounds, or Jeopardy-style challenges) has decades of research behind it showing how repetition with feedback strengthens long-term retention.

The magic is in the loop: recall → feedback → reflection → retry.

With MCP, that same loop can now become code.

Imagine a Trivia Server built on top of MCP. It exposes capabilities like get_question, validate_answer, explain_answer, and log_score, with policies that define what a learner can do — maybe you can read:question_bank and submit:answer, but you can’t peek at the answer key or modify the dataset. Each interaction creates a trace. Each trace becomes feedback. Each round becomes data for reflection and improvement.

But this goes deeper than play. The French cognitive scientist Pierre Rabardel called this instrumented learning — the process by which learners transform artifacts (tools, technologies, or systems) into true instruments for thinking. In his Instrumented Activity Situation model, learning isn’t just about using a tool; it’s a dynamic relationship between three elements:

- the learner (subject)

- the instrument (the tool once internalized and adapted)

- and the learning goal (the object of activity).

Rabardel argued that mastery means developing “utilization schemes” — mental models and behaviors that make a tool part of your cognition, not just your workflow.

That’s exactly what MCP enables. You’re not just earning points; you’re generating context-relevant insights about curiosity, comprehension, and growth. The protocol becomes part of how you think, not just what you use.

And this same principle extends far beyond trivia. Designers can explore brand systems with scoped access to live style guides and repositories — learning how real design systems evolve in practice, not theory. Journalists can safely experiment with datasets and querying information, Policy students can simulate civic databases, observing how small interventions ripple through complex networks.

Different fields, same foundation: safe, scoped, contextual, measurable learning.MCP transforms abstract lessons into operational experiences — places where curiosity and rigor can finally coexist.

Pedagogy, meet infrastructure

If all of this sounds a little familiar — the scaffolding, the sandboxing, the feedback loops — that’s because the best parts of MCP aren’t new ideas. They’re the technical expression of what decades of learning science have already proven works.

Take Lev Vygotsky’s idea of the Zone of Proximal Development — that sweet spot just beyond what a learner can do alone. In MCP, that “zone” becomes a set of permission stages. The environment adapts as competence grows: learners start with read-only access, unlock simulation, then gain the ability to make safe, reversible changes. Agents or mentors provide just enough support to bridge each gap.

Or Seymour Papert’s constructionism — the belief that people learn best by building meaningful artifacts. MCP makes that real. Learners don’t just hear about systems; they interact with them. They build prototypes, write code, deploy containers, and watch their work come alive inside safe, instrumented environments.

David Kolb’s experiential learning loop — Experience → Reflect → Conceptualize → Experiment, is practically built into the protocol. Every learner action is logged, every reflection is captured, every iteration can be replayed and refined. It’s learning as a system, not a script.

And of course, Amy Edmondson’s work on psychological safety still holds the foundation: learners can take risks without fear. In MCP, safety isn’t just cultural; it’s architectural. Versioning, rollback, and explicit guardrails make exploration the default, not the exception.

These aren’t academic footnotes tacked onto a shiny new framework — they’re the very DNA of how MCP operates. We’re not borrowing from learning theory; we’re encoding it into infrastructure.

Stop shipping courses; start shipping context

For too long, ed-tech has been built around delivery: upload the video, push the quiz, move the learner along. But learning isn’t about consumption — it’s about interaction.

MCP flips that equation. Instead of designing lessons, we design environments. Environments where learners can think, act, and reflect safely inside systems that behave like the real thing.

Think of it this way:

- CI/CD pipelines become learning pipelines: Observe → Simulate → Practice → Launch.

- Observability dashboards turn into learning logs, capturing reflection and progress.

- Version control tracks not just code commits, but moments of understanding.

- Containers and sandboxes become the new classrooms — self-contained, resettable, endlessly explorable.

This isn’t a shinier LMS. It’s a re-architecture of how learning itself happens — from content delivery to contextual participation.

In other words, MCP doesn’t teach you about systems. It teaches you through them.

Curiosity as a core principle

At its core, engineering and education are chasing the same goal: building systems that can evolve.

MCP gives us a framework for that — a formal way of saying, “Go ahead, learn in production. Just… maybe not our production.”

Because when learning mirrors how humans actually grow — by doing, failing, reflecting, and iterating — we don’t just build better developers. We build better systems: ones that adapt, self-correct, and (if we’re lucky) throw fewer tantrums than we do.

This isn’t about swapping humans for AI. It’s about teaching them to share the same sandbox without biting each other. A partnership where both learner and system are part of the same infinite feedback loop: build, break, learn, repeat.

MCP isn’t just a protocol for machines — it’s a protocol for curiosity.

And honestly, the world could use a bit more of that right now.